Climate

1658252450.jpg)

Sunday, April 29, 1979.

Eleven year old Bishnu Gautam was on his way to school atop a hill about one and half hours walk away from his home in Khandrung, Ilam. They were four of them: Bishnu himself; his younger brother; his first cousin, Hom; and Kamal.

Minutes before they got to the school, the rain began to pour suddenly. The boys started running towards the nearby Peepal tree shade called Chautari where the locals often rested.

And, the worst happened – then and there.

A massive thunderbolt struck the tree and electric jolt tossed Hom a few feet up in the air. The 16-year-old landed several feet away.

"Hom, my brother and Kamal were already at the Chautari,” recalled Gautam. "I was paces behind."

Shocked, terrified and nervous, three of the kids ran to school. The teenager was left lying flat on the ground under the Peepal tree. The giant tree itself was burnt badly and died days later.

At school came the bad news: Hom was dead.

In Nepal, particularly in the rural parts, thunderbolts kill over a hundred people every year. A large number carry on with lifelong injuries and trauma, including disabilities like permanent hearing losses. Often, their living costs go up.

Bishnu Gautam, currently The Rising Nepal daily's chief reporter, is one of them. While his friend Kamal instantly lost his hearing Gautam's right ear hearing steadily declined. He uses a special hearing aid on his left ear.

The device costs roughly 500 thousand rupees and needs to be replaced every four to five years, said Bishnu.

Risk reduction

According to Nepal government’s Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR) Portal, 27 deaths were reported in the last 30 days of June and July, which is more than flood and landslides combined. Nepal isn’t the country with the highest number of lightning events; yet it ranks amongst the top five in fatalities.

“The data DRR collects is only of direct hits; the number may climb to scary levels if ‘indirect electrifications’ are counted,” Dr Shriram Sharma, Nepal's top lightning expert, also the chairman at South Asian Lightning Network (SALNet) told NepalMinute.

“People can get electric jolts and electronics can get destroyed by the lightning tens of kilometres away that is indirect electrification.”

"Tin roofs, mud walls and lack of lightning protection measures in rural households contribute to killings and injuries caused by lightning and thunder bolt strikes,” he added.

A US disaster risk reduction campaign says: “When thunder roars, head indoors."

In Nepali context, however, there is a caveat. It's best and safest to move indoors only if the “building is protected”.

“People are supposed to stay or rush indoors when there is lightning, but in the absence of proper lightning protection systems across Nepal, particularly in the rural areas, that very safety protocol – remaining indoors – may cause the real damage,” said Sharma.

"When you do not have a safe shelter, there is nowhere you can go."

What can be done to lower the human casualties and sufferings?

“We can’t stop the disaster but our studies indicate a pattern in Nepal's lightnings. That pattern will be useful to mitigate the suffering,” said Sharma.

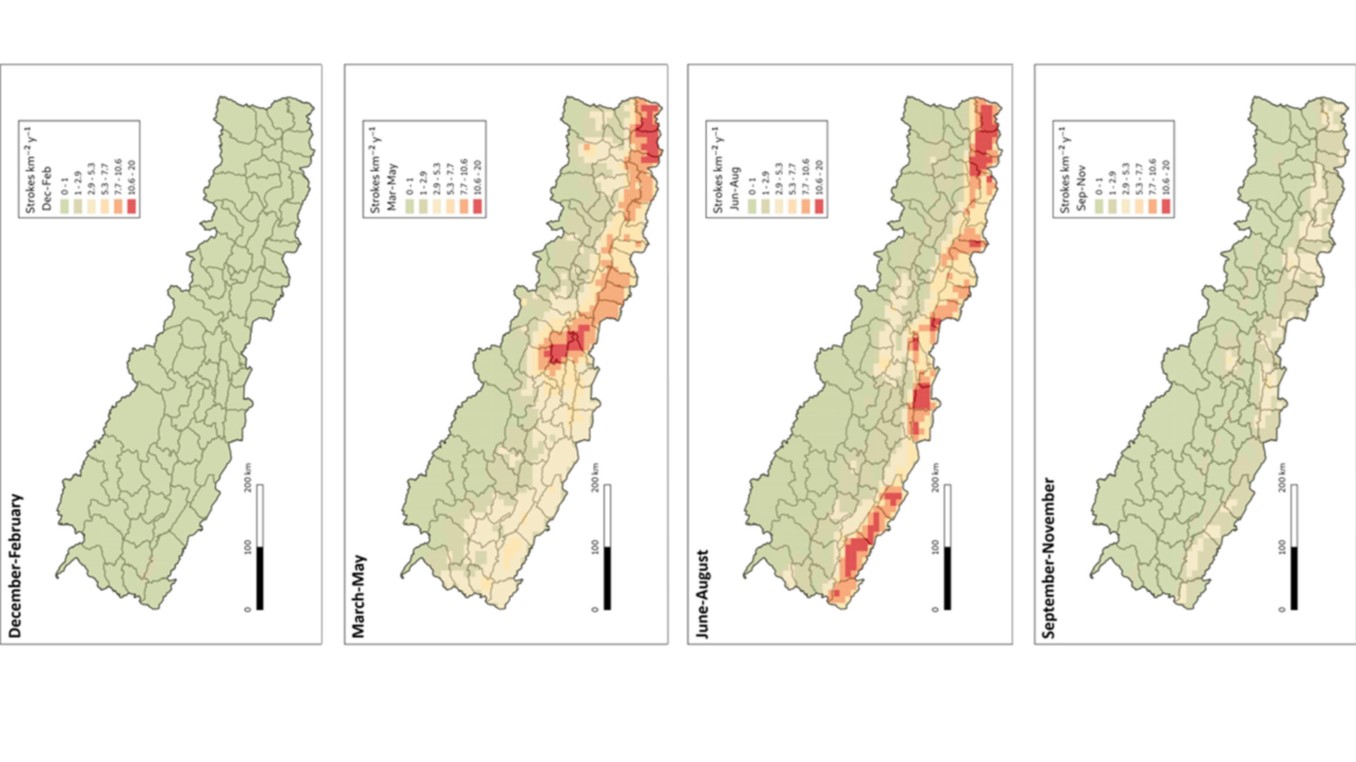

While lightning events peak during the pre-monsoon (April to June), middle and south-eastern parts of Nepal are where lightning strikes the most.

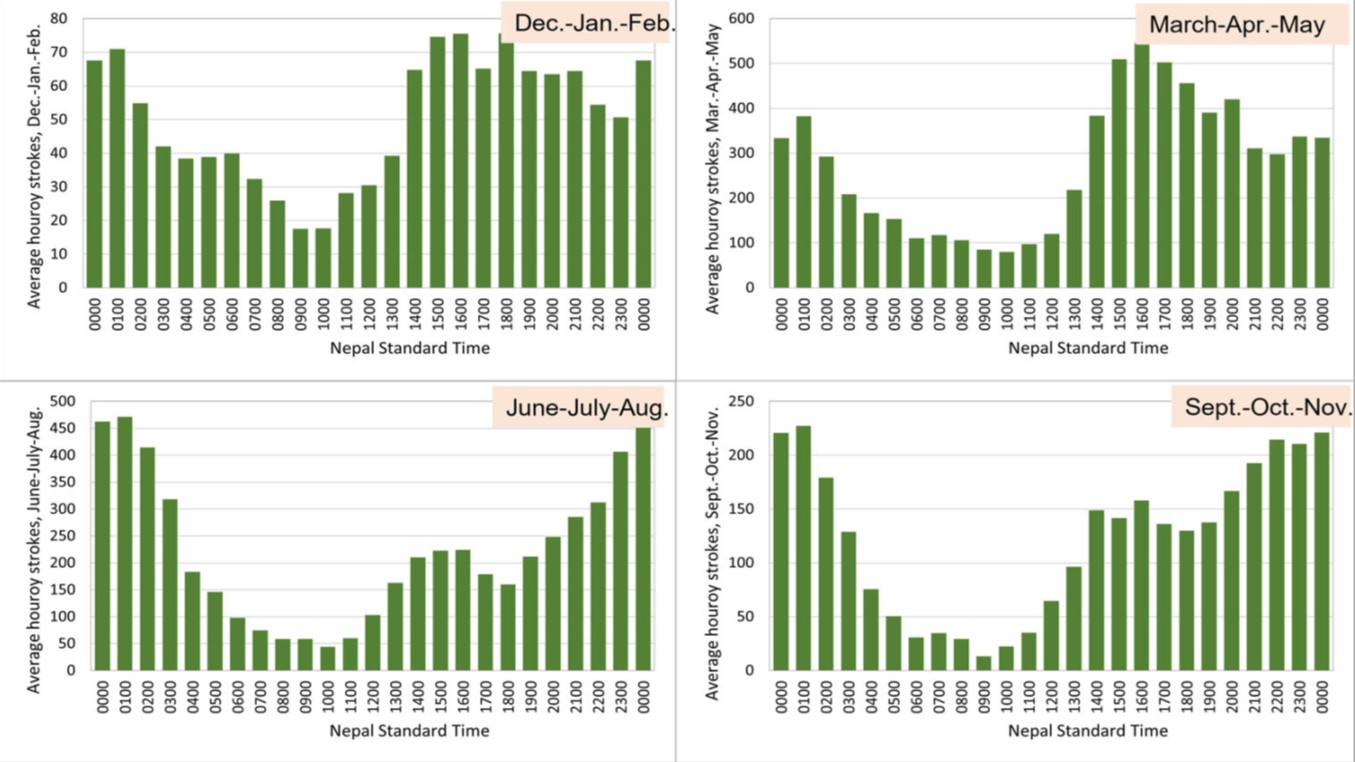

"Early mornings and hours before 12 pm are the safest time of the day, in that most lightning incidents occur in the afternoons and evenings.

“This particular piece of information can be very instrumental for scheduling the outdoor agricultural activities, avoiding thunderstorm hours,” said lightning expert Sharma.

According to Sharma, lightning strikes have a pattern by geography. "In the hilly areas, lightning tend to occur from afternoon till evening. In the lower plains, however, more lightnings happen late at night."

“Next, we also need to educate the people to install proper lightning protection system in every building.”

“I’ve seen big schools and business complexes putting a lightning rod in the middle, but that is not enough considering their huge footprint,” said Sharma.

What needs to be done?

He added: “Proper policies need to be formulated by the government. The government has hired a lot of civil engineers, structural engineers in each municipality and rural municipality after the 2015 earthquake, but none of the 753 local levels employ any electrical engineers.”

“Electrical engineers aren’t just for lightning protection; we have seen lots of fire incidents caused by short circuits. So, why not hire one in each local level too?”

His expert colleagues suggest that the government and the community members alike need to take "urgent precautionary measures" such as intalling lightning protection system in every house and building.

Dr Prem Raj Dhungel, physicist and executive director at SALNet: “Every structure has to have a lightning protection system in place. It doesn’t need any sophisticated technology, we can make residential houses, commercial buildings and all tall structures safe simply by using metallic rods and wires to protect from direct hit by lightning.”

“But for indirect electrification, one can opt for ‘surge protection device’”

Being costly, this device can be employed by businesses to protect high value assets.

Nepal does not have any provision of electrical auditing.

“We all do earthing; we put salt and then bury the wire in the salty soil for better conductivity.”

“But we never check it, the salt and moisture will have already snapped the wire and the earthing is anything but functional.”

“Therefore, an electrical auditing should be carried out every few years to check any kind of vulnerability,” Dhungel said.

What to do if lightning starts?

- Head indoors of cars or building, the building must be lightning protected;

- Get out of water, if you are in river or wet field;

- Do not take shelter under a tall, isolated tree or poles;

- Do not take bath or use water even inside the home;

- In the open field, crouch and make yourself as small as possible;

- Turn off all the electrical equipment to protect them.