Opinion

All great empires eventually burn out. Primarily on account of two factors – military overreach and domestic turmoil aggravated by a loss of faith in imperial money, among other institutions, as historians have often noted.

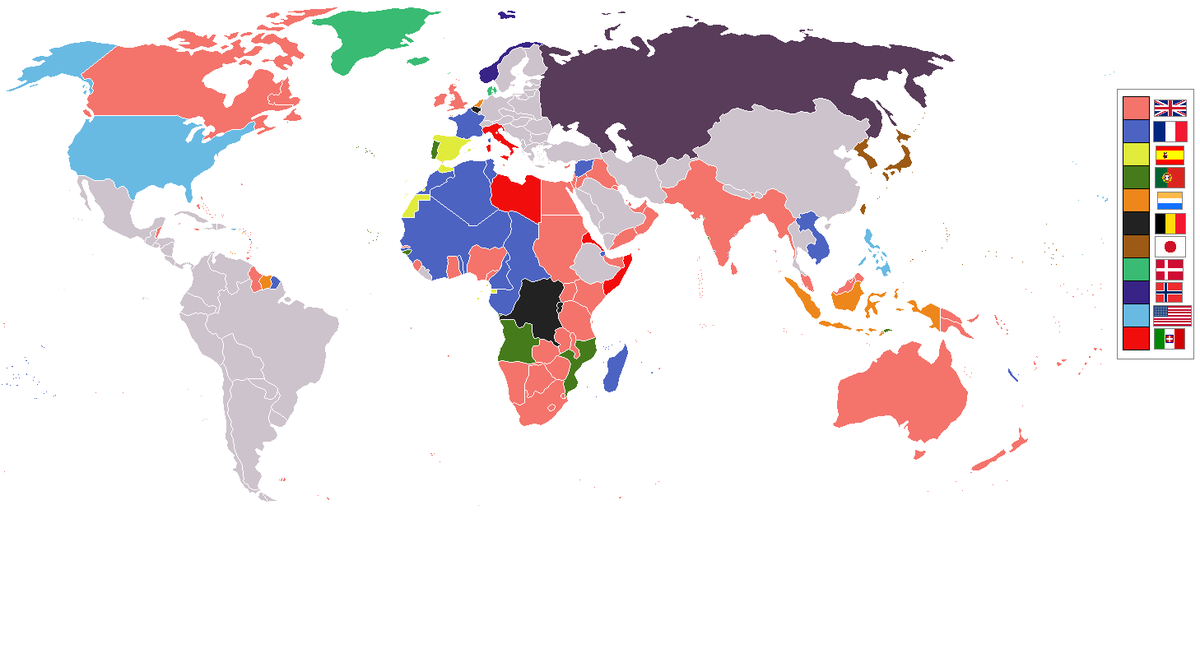

Ever since the invention of gunpowder and the circulation of money, either or both appear to hold fatally true: be it the case of the Roman Empire (31BC-1453CE); the Song and Yuan dynasties in China (960-1368CE); the Mongol Empire in Eurasia (1206-1368CE); the Ottoman Empire in South East Europe and Northern Africa (1300-1922CE); the Mughal Empire in Central and South Asia (1526-1857CE); the Spanish, Portuguese, German and Italian colonial conquests (1492-1999CE); the British, Dutch and French East India Companies in East and South Asia (1600-1873CE); and even up until the demise of the Soviet Union (1991CE).

Obviously, empires do not rise or fall overnight. But they do seem to have a life span. Sir John Bagot Glubb, the celebrated late British soldier and influential author, determined the average age of latter-day empires at 250 years. “After that, empires always die, often slowly but overwhelmingly from overreaching in the search for power,” he noted.

Interesting, for America - today’s pre-eminent global power born in 1776 - that 250 year milestone is fast approaching, i.e., in the year 2026, four years from now.

America generally refuses to see itself as an empire in the traditional mould. Americans even take extra pains to distance themselves from the colonial-era horrors inflicted by their western allies not too long ago. In fact, American popular culture has always celebrated the underdog, creating icons of those who stood up to the ‘system’ and brushed with the law to eventually win justice denied – in real life as well as in art form.

The US military might

All that is well and dandy for Americans. But few understand why the rest of the world sees them differently. The US today runs a national debt surpassing US$ 30 trillion – an 800 percent increase since 1989. Yet it still operates 800 plus military bases in 70 countries around the world. This is not counting Special Operations Units stationed in 130 countries. From the long arc of history, this certainly appears like military overreach.

Most countries stringently adhere to a debt ceiling, instituted by national law, in order to maintain fiscal sustainability. In contrast, the US has revised its debt ceiling 78 times since 1960, roughly in line with deficit spending accumulated year upon year. Of the nearly US$ 3 trillion in global circulation today (M1), over 80 percent was printed after 2020.

Unlike the rest of us, the US can get away with this by virtue of the dollar’s status as the world’s preferred reserve currency. Domestically, US politicians across the spectrum applaud the benefits of deficit spending – growth, employment and consumer spending. But if any individual were to adopt this as a business model, it would be stridently dismissed as a ‘Ponzi Scheme’.

What is good for the US is not necessarily also good for the rest of the world. This is particularly true when two-thirds of all currency reserves and close to half of the world’s debt is denominated in US dollars. When the US floods its market with cheap dollars (a.k.a. “quantitative easing”) the demand for goods and services soars to the point of inflating prices across a globalized world. When the US hikes interest rates (a.k.a. “quantitative tightening”), the value of other currencies falls against the dollar, and thus again inflation spikes in import-dominant economies.

And now the world is sobering up to another reality: the ‘weaponization’ of the dollar. The frequency with which the US has been applying sanctions and tariffs in the pursuit of its foreign policy objectives has many countries worried. At this rate, anyone could find themselves in America’s cross-hairs next.

There is a noble history that dates back to American independence and disputes over taxes between the colonists and their English rulers that led the drafters of the US constitution in 1787 to adopt tariffs and sanctions as legitimate political and economic instruments.

But the question must be asked – did enlightened minds like George Washington, Benjamin Franklin and Alexander Hamilton ever intend those provisions to someday allow the US Treasury to expropriate Afghanistan’s entire foreign currency reserves, knowing very well that a humanitarian crisis would ensue? Or to punish all Russians for their president’s adventurism and gall to challenge the post-World War II global order?

New world order?

According to an analysis by the Economist’s Intelligence Unit (EIU) last May, only 16 percent of the world’s population lives in countries that support western-led sanctions against Russia. Over two-thirds live in countries that have either adopted a neutral position over the war in Europe or have opposed statements condemning Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

But now that the naysayers have made their positions clear, a bigger fear lingers – will the US hit them with secondary sanctions? Will they, too, be cut off from SWIFT (the global banking payments system), barred from borrowing from international capital markets, or even from engaging in global free trade? Does George W Bush’s famous Iraq war maxim “you are either with us or against us” still prevail?

For some time now, and especially after the crash of 2008, world leaders have been weighing the pros and cons of an economic order denominated in US dollars. But credible moves to wean their economies off the greenback in a viable alternative have been few and far between. The war in Europe and the recurring recklessness of the west’s self-centred response to global crises (vaccine nationalism?) has provided fresh impetus to the debate. But will it be for real this time?

The recent buzz around BRICS suggests that it just might be. Up until recently Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa, acronymed BRICS, were individually labelled as ‘emerging’ economies. Look them up now and one will see how they collectively represent over a quarter of the world’s land surface as well as two-fifths of the global population and economic output. Look them up again in a year or so from now and, in all likelihood, Iran, Argentina, Saudi Arabia, Turkey and Egypt will also have joined.

This should not be too hard to fathom. After all, 20 countries produce 90 percent of the world’s tradeable commodities. For far too long, a dollar denominated monetary regime has deterred them from collectively realizing their full potential and claiming their rightful place in the global order.

Interestingly, none other than Henry Ford, the great American entrepreneur and business magnate, laid out his vision 100 years ago on how a commodity backed currency (‘energy currency’) could break the banking elites’ grip on fiat money and global wealth to prevent future wars. Too bad there were few takers back then.