Science & Technology

Two years ago, Chandrika Pun Magar, a student at Tri-Chandra Multiple Campus, lost her OPPO F9 phone while boarding a microbus from Ratnapark to Maitidevi. She had only had it for a month.

She reported the case to the Teku Metropolitan Police Complex. After much persistence, the Kathmandu Valley Police Office’s CCTV monitoring unit gave her access to the footage from the Ratna Park area, starting around the time she got in the vehicle that day.

After poring over the recordings for hours, she and her sister eventually caught the thief and turned him over to the Durbar Marg Police Circle. The thief was detained for more than a week before being released.

During interrogation, the thief told the police that his companion had taken the phone to India that night to sell it on the black market. Pun was told by a police official at the station that recovering his stolen phone was unlikely since its IMEI may have been changed.

It has been more than two years since she reported the missing phone to the Teku Metropolitan Police Complex. She has not received any phone calls or messages from the law enforcement agency.

Nepal started IMEI registration in 2016, but the $7 million MDMS technology did not start until a law made it possible in 2018.

Theft control

The Mobile Device Management System (MDMS), which is supposed to stop people from stealing phones, is not keeping up with smart thieves.

According to Nepal Police data, only about 13 per cent of phones that were lost in the last fiscal year have been found. Only 5,310 of the 40,996 phones that were reported lost or stolen in Nepal have been found and given back to their owners.

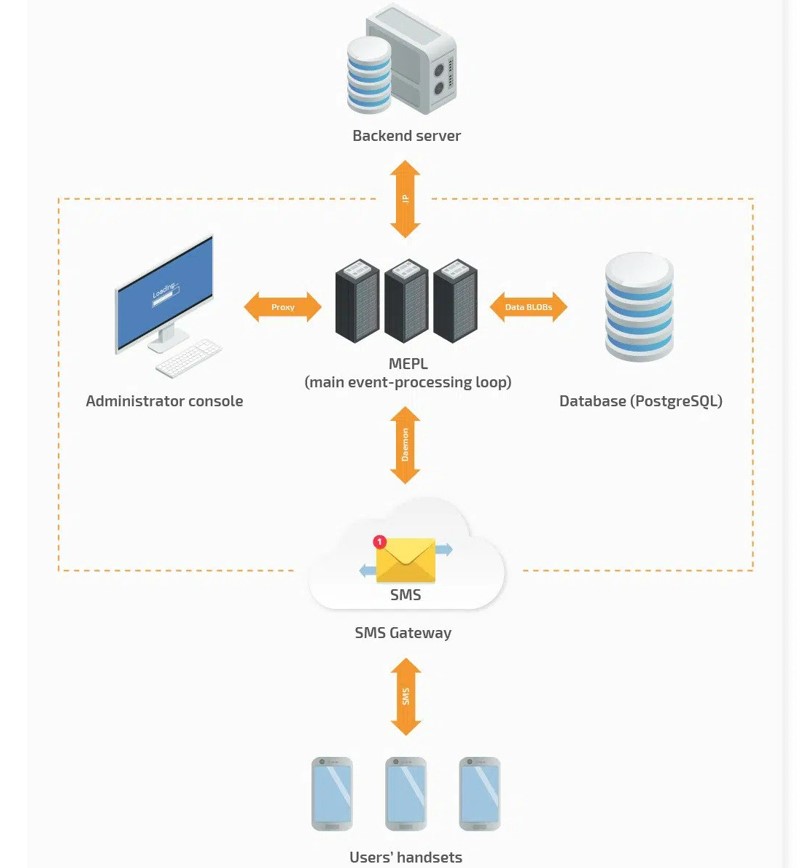

The Nepal Telecommunications Authority (NTA) uses MDMS to track IMEI, which is used by the Nepal Police to put the device on a blacklist. International Mobile Equipment Identity (IMEI) is a unique 15– or 17-digit identification number used on phones with GSM technology for identification. CDMA phones have their own equivalent of the IMEI.

Talking to NepalMinute, the Deputy Director at NTA, Achyuta Nand Mishra, who also oversees the MDMS, said: “MDMS makes it harder for people to steal mobile devices. But we are not saying that it will go to zero."

If a phone is stolen, the thief can flash the device. Flashing is an illegal process that changes the phone's IMEI, so it can be registered in the MDMS as a new device.

Grey market: a real headache

On the surface, the MDMS appears to be a useful technology that provides a safety net. However, a closer look would reveal that the government's attention is actually elsewhere.

In an attempt to offset the shrinking revenue due to the slowdown in economic activity brought on by the COVID-19 epidemic, the government on December 30, 2022 announced the introduction of MDMS and an 18 per cent customs duty on phones brought by Nepalis returning from abroad.

However, it rolled back its decision to enforce the MDMS following widespread criticism.

According to the NTA, MDMS has shown that nearly four million grey market phones have been used in Nepal in the last three and a half months. These are phones that have been “smuggled into Nepal”, as opposed to the 1.5 million legal phones.

NTA Deputy Director Mishra estimates that Nepal loses about Rs2 billion in monthly tax revenues due to such activities.

Telecom towers equipped with MDMS technology will disable unregistered mobile handsets. One can technically use the phone, but any SIM card or eSIM in the phone will not be functional.

What is the solution?

Referring to the number of phones being brought back by Nepalis working abroad as "minuscule", Mishra added: "The real problem is not the phones being brought in by Nepalis returning home from abroad, but the phones that are being smuggled in by illicit dealers."

The NTA official insists that enforcing the MDMS is the only viable option. Smuggling contraband cellphones has become a “serious issue."

"The government should decide how many phones Nepalis can legally bring home," Mishra said, arguing that the government should work with the customs department to establish a uniform tax rate and than scaring the public with MDMS.

Mishra denied that the NTA tried to put the MDMS in place to help people who import phones.

“These are the rumours spread by people in the black market who profit from smuggling the devices,” said Mishra, who oversees the MDMS implementation. “The importers pay the tax and bring the phones in, so we can say that the government and the people are the ultimate beneficiaries.”

Does the public stand to gain?

There is considerable public debate over what other possible utility values the complete implementation of MDMS would provide to customers, given that the partial implementation is already serving its purpose (tracking stolen devices, device misuse, etc.).

“Mobile phones have now become an important part of a person’s lifestyle,” said Mishra, explaining that "keeping a safe phone is the greatest method to safeguard your privacy" because so much personal information (including biometrics, financial details, and more) is stored on people's mobile devices.

In other words, he added: “You can't assume that a phone you bought from a smuggler hasn't been hacked.”

Also read: Nepali migrant workers' threat prompts govt to forsake MDMS