Environment

Astronomical observatories have been located in cities for centuries. However, as electric lighting became more common in urban areas, working observatories in Europe and the US began to relocate to the suburbs and to mountain peaks.

Rapid growth in light pollution has pushed them farther and higher. Astronomers and amateur skywatchers in Nepal have also noticed the effects.

Saroj Raj Shahi, the manager of the BP Koirala Observatory, the only national observatory of Nepal, said: “The telescope mounted on the observatory cannot be pointed at the sky above Kathmandu due to nighttime glow.”

The observatory is located on a hilltop at Nagarkot, a small tourist resort 30 km to the east of Kathmandu.

1674723656.jpg)

Because of the nearby higher hill to the east, the glare of Kathmandu to the west, and local light pollution from hotels in Nagarkot to the north, Shahi claims that observers are limited to either observing spectacular things in the universe or a very tiny area of sky.

Housing construction in the valley's periphery over the past decade has "increased the intensity and extent of the glow and diminished the beautiful, dark sky," he observed.

According to the 2016 ‘World Atlas of Artificial Night Sky Brightness’, 80 per cent of the world’s population lives under skyglow, which seems not to be slowing down. It can be analogous to Nepal, given the trend of migration to cities like Kathmandu in the past decade.

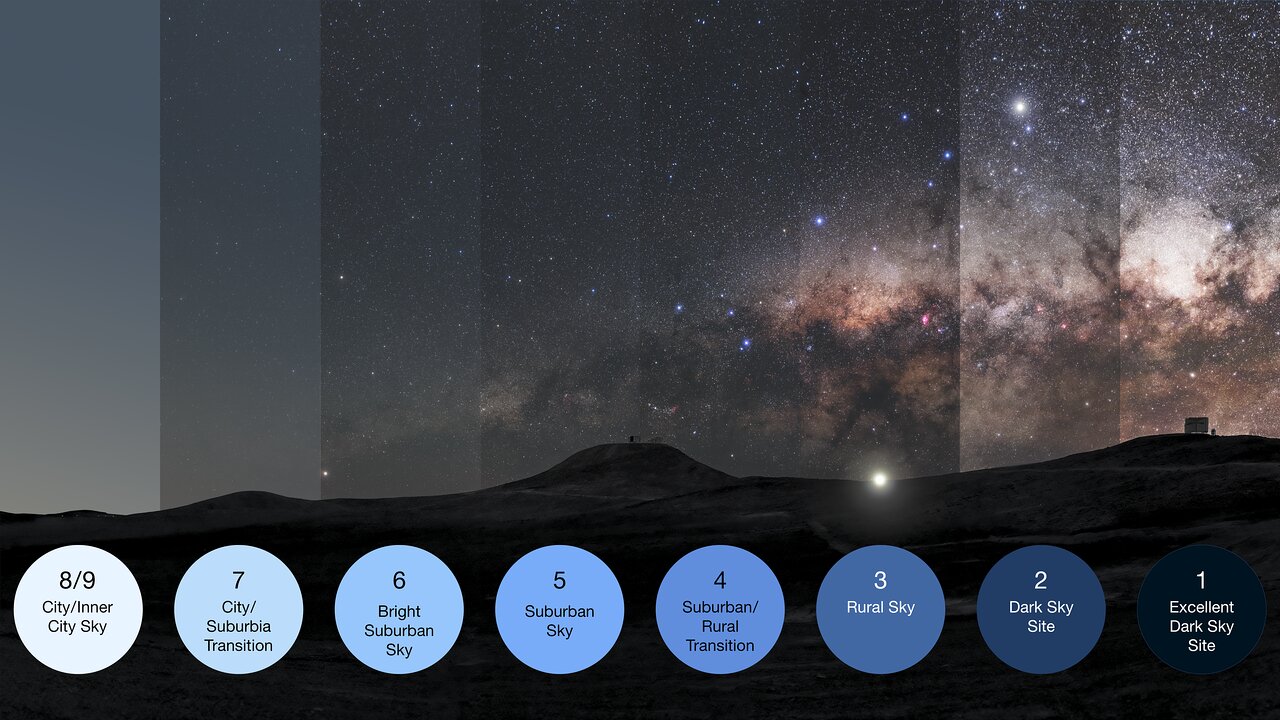

Now, people have to go to the Himalayas, far from any city, to observe the band of Milky Way.

In contrast to odour, glare, and airborne particles, light pollution is rarely addressed since its effects are not immediately apparent.

Scientists believe that this, coupled with the decreased cost of lighting like LEDs, has led to excessive illumination in cities around the world, resulting in glare in the night sky.

The detrimental impacts of light pollution on stargazing are documented in a 2023 research published in Science Journal

With the data, the researchers of the report concluded: “Trends in the data showed that the average night sky is getting brighter by 9.6 per cent every year from 2011 to 2022, which is equivalent to doubling the sky brightness every eight years.”

Even though the problem is not being formally recorded, astronomers in Nepal like Shahi can feel it. This is because there appears to be a spatial bias in the reporting, which means that citizen scientists primarily make the number of reports made on the database for the research of the developed world.

Experts worry that future generations will not see the point in studying astronomy and space travel if they cannot see the stars.

"I don't think, it will lessen the interest in young children," said Shahi, "but yes, it is true, to see the genuine stars away from their books and digital displays, one needs to manage a leave for a day or to climb to the hills at the edges of the valley."

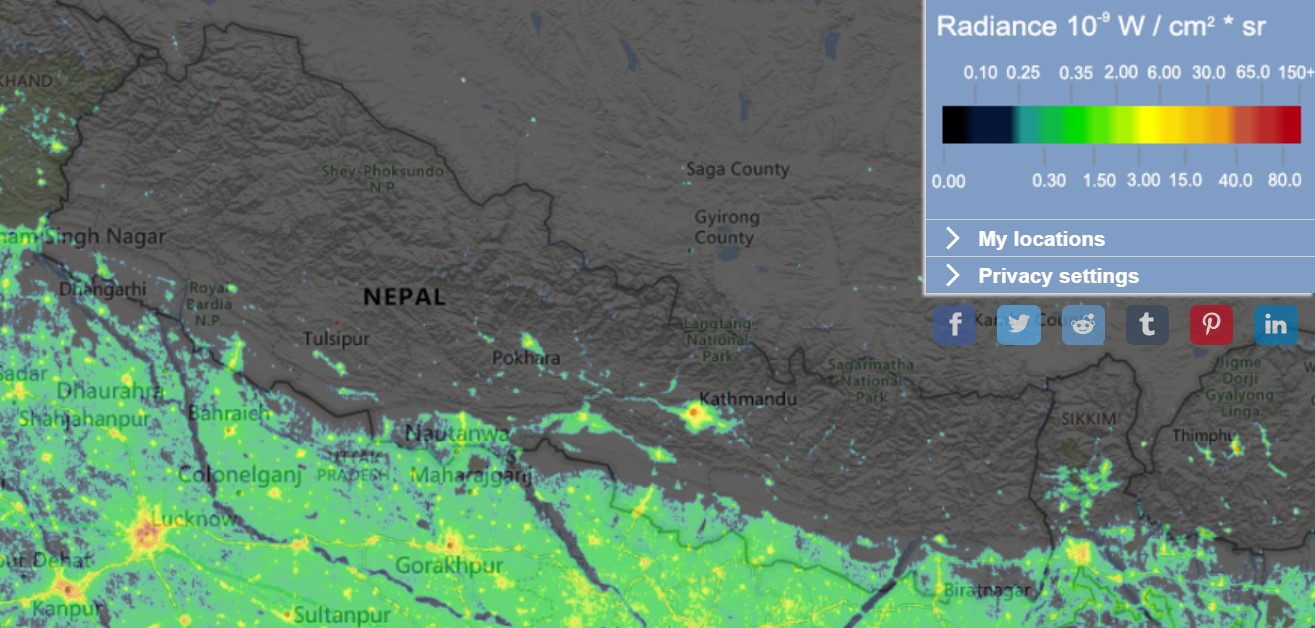

Based on data collected by NASA's VIIRS satellite, which monitors the Earth in both the visible and infrared spectrums, lightpollutionmap.com, a website that publishes statistics and observations on light pollution, has found that Nepal's light pollution (luminosity) has increased by 2.28 per cent over the past decade, which is surprisingly higher than India's 1.92 per cent increase during the same period.

The gloomy sky is still present over most of the highlands and Himalayas of Nepal, but it is threatened by rapid and unplanned development.

The chart shows a worrying trend in the brightness level of cities and urban centres in Nepal, including Kathmandu, Butwal, Nepalgunj, Birgunj, and Biratnagar, with some places reporting a spike of more than 30 per cent.

These easy steps, however, can be taken to mitigate the effects of light pollution:

- Only use lighting when and where it’s needed

- If safety is a concern, install motion detector lights and timers

- Protect all outdoor lights the right way

- Keep your blinds drawn to keep light inside

- Use only lights that shine down inside and out