Nature

An afternoon in late August inside the Langtang National Park, around 100km north of Kathmandu.

As the sun breaks through the monsoon clouds, enigmatic mushrooms, dormant for months, have awakened to seize their long-awaited splendour.

Laxmi Tamang of Thulo Bharku, Rasuwa, having collected those enigmatic fungi from the lush green park forests, was busy serving mushroom cuisines to trekkers and pilgrims heading for Lake Gosaikunda (4,380m).

Guided by generations of wisdom, Tamang knows how to identify the edible ones, harvest and cook them. And, of course, sell them too.

“We know which ones are edible and which ones are not edible [poisonous],” she said, smiling. The white and yellow mushrooms, laid out to sundry in front of her makeshift shop at Cholangpati (3,600m), dazzled.

Mushrooming - yes literally mushrooming - in their variety and colours, these colourful, wild fungi can be seen dotting the Himalayan slopes, valleys, and even plains across southern Nepal all year round, but more so during monsoon.

Mushrooming - yes literally mushrooming - in their variety and colours, these colourful, wild fungi can be seen dotting the Himalayan slopes, valleys, and even plains across southern Nepal all year round, but more so during monsoon.

Some of these are edible, others are not, and yet others may be very poisonous as nearly 10 per cent of mushrooms are poisonous worldwide, experts warn.

Up for grabs among these wild varieties are the magic mushrooms – a type containing hallucinating chemicals like psilocybin or psilocin. But, beware, you may not be certified, or qualified enough, to identify the shrooms, pick them out and devour!

And then there's the most sought-after variety: Yarsagumba. Also known as the caterpillar fungus, Yarsagumba is renowned for its incredible health benefits, including aphrodisiac characteristics and the ability to fight cancer and stroke. Every season, it is the main draw for mushroom foragers.

Like many Nepalis, I’m far from knowledgeable about these mushrooms or fungi, the most widely-occurring yet understudied botanical species on earth. Only 14,000 of the nearly 4 million varieties have been reported as of now, according to researchers.

I don’t know which ones are edible, which ones are poisonous - and which ones are the magic potions that give you a high for a couple of hours. So you’d better be cautious.

My favourites are the red, yellow and white mushrooms that I got to see and savour during my recent trek to Lake Gosaikunda in Langtang National Park – thanks to local hosts like Laxmi Tamang and Rinchen Tamang. Or the red Stereum sp, a wood-decaying fungus, that I got to enjoy at Dongyang along the Tsho Rolpa Glacial Lake, Gauri Shankar trail back in June.

Or the chocolate-coloured ones that we were served with pasta above Namche Bazaar en route to Everest Base Camp in the midst of Covid-19 in October 2020.

Or another red variety with a golden flipside which we collected and gave to the lodge lady but were unfortunately never served at Magin Goth, above Kutumsang, along the Sundarijal-Gosaikunda trek almost ten years ago.

Serving us plain potato curry, the lady cleverly saved those for later.

The spicy curry of the fresh and super-organic wild mushrooms is the only cuisine I enjoy with rice during my Himalayan treks; I don’t particularly like the bland potato or the other curries that our kind hosts painstakingly prepare and serve there.

Back home at Mulpani, Kathmandu, my favourite is Shiitake mushroom (Lentinula edodes), an East Asian native that is nowadays also grown by farmers across the hills and plains of Nepal. Especially its curry laced with garlic, ginger, hot Sichuan or cayenne pepper and other spices!

During off seasons, the widely available White Straw, White Button, or Oyster mushroom, available in the veggie markets of Kathmandu, or the dried black fungi sold in supermarkets, help.

During off seasons, the widely available White Straw, White Button, or Oyster mushroom, available in the veggie markets of Kathmandu, or the dried black fungi sold in supermarkets, help.

My love for Shiitake mushrooms started blooming in 2008. Then, after reading about its seed availability at Imadol, Lalitpur, I didn’t just farm and successfully harvest the fungi from my Uttis (Nepali Alder) logs but also savoured and shared them with relatives.

I’m delighted to know that I’m not alone. There are numerous other folks – all over Nepal and beyond – who are connoisseurs of wild mushrooms.

Even around the foothills of Kathmandu Valley, every monsoon, I've seen locals venturing into leech-infested forests for mushroom hunting, plucking red, brown, yellow and white mushrooms for lunch and dinner.

Even around the foothills of Kathmandu Valley, every monsoon, I've seen locals venturing into leech-infested forests for mushroom hunting, plucking red, brown, yellow and white mushrooms for lunch and dinner.

Yet, year after year, news reports of people tragically dying or getting hospitalised after savouring fresh mushroom curry and rice continue to hit the headlines.

Mushrooms or fungi are believed to offer the vital lifeline for not just trees and vegetation but also the ecosystems in the planet’s complex web of life. Without them, the ecosystems cannot survive.

To humans like you and me, they offer much-needed nutrients, including protein, vitamin D and antioxidants. Some varieties possess immense medical value too.

Last year, a group of mushroom enthusiasts from the USA, Mexico and Nepal visited Sagarmatha National Park, home of Mount Everest, to study a wide variety of mushrooms. They were part of a Mushrooms Tourism initiative by Rick Silber from Washington DC, Nepali mushroom expert, or mycologist, Shiva Devkota.

Devkota, a PhD from Bern University, Switzerland, is currently working as a scientist at the Global Institute for Interdisciplinary Studies (GIIS), Lalitpur, as well as the Himalayan Climate and Science Institute, Washington USA.

He said the trip with a "fusion of mycological knowledge and practical expertise was highly productive, resulting in participants observing around 156 distinct mushroom species along the trail without venturing deep into the woods.”

Astonishingly, their catch also included the rare Amanita innatifibrilla and Tremella salmonea which are also rare in neighbouring China. They also documented a new species Amanita tullossiana, which was first discovered in 2018 in Uttarakhand, north India.

The expedition firmly projected Nepal Himalayas as a mushroom hotspot for tourists, explorers and researchers alike and has opened a new avenue for tourism. The concerned bodies like the Nepal Tourism Board should promote such initiatives as they are formed to promote and highlight tourism activities, said Devkota.

“We agreed that if tourists can be invited to Nepal to observe tigers, rhinos, and elephants, why not also showcase the world of mushrooms?” Devkota, a native of Pokhara - another mushroom hotspot - said.

After the success of the Sagarmatha trip, a similar mushroom trek took a group of international mushroom enthusiasts around the Annapurna Circuit in Gandaki Province this past monsoon. “And it went very well,” he added.

The next Mushroom Trek in the Nepal Himalayas is due next monsoon, he said.

With thousands of known and unknown mushrooms, now I wonder, what benefits Nepalis and Nepal can reap from these multitudes of colourful wild varieties.

Experts say mushrooms could offer immense economic opportunities.

One way of harnessing the potential, according to Devkota, is by applying “biotechnological methods to domesticate these wild mushrooms, cultivating them in controlled environments, or on suitable substrates.”

That way, he said, “we can tap into their unfolded food and medicinal value.” Such practice can provide other start-ups to bring essential nutrients and potential health benefits-based enterprises, he added.

Additionally, he suggests the promotion of mushroom-related activities, such as the recent Mushroom Tourism trips and cooking and tasting events. He thinks that would go a long way in attracting ecotourism, creating new revenue streams for local communities, while celebrating Nepal's rich fungal heritage.

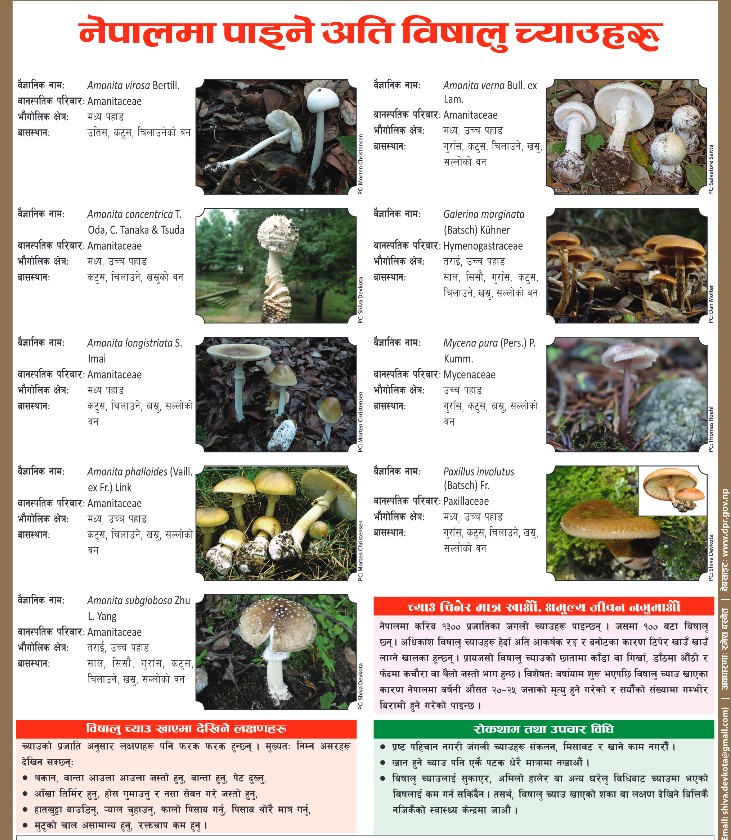

Yet caution is needed. For, of the nearly 1,300 types of mushrooms studied by Nepali mycologists, recent research found 159 edible, 74 medicinal and 100 toxic.

That’s why “we should also maintain certain precautionary measures because mushroom poisoning is another serious public health issue in Nepal,” Devkota said. “Utilising indigenous local knowledge and adhering to the principle of ‘eat only those mushrooms that have been consumed for years’ can help mitigate the risk of poisoning.

Also Read: 'Nobody should make us tigers' prey'