Science & Technology

As smart devices flood the market, people with vision problem are beginning to see solutions coming their way in a sci-fi fashion. The technologies have the potential to intrigue the uninitiated.

Here is a review of five that promise the vision-impaired a fuller interaction with the world as well as the experiences of assistive technology users in some Nepali schools.

1. Speech-to-text software

Speech-to-text software recognises natural speech and turns it into a written text. Users can tell the tool to write and read texts for them with a surprising accuracy, reportedly up to 99 per cent. The technology breaks down speech into phonetic sounds, maps them to a database and returns their fittest written equivalent for use, say, at home or school.

Dragon Dictation, J-Say Pro, and Windows Speech-to-Text are the most popular voice recognition and transcription solutions available in the market. Their prices range between $500 for professional and enterprise versions to $49.99 for the basic version.

One can try writing with voice on a Microsoft Word as well. Open a Word file, hold down the Win key and press H for the dictation toolbar to appear at the top of the screen. You can then begin dictating.

2. Finger Reader

The Finger Reader is a recent innovation that allows people to open a book, place their finger on the page, and scroll as the device picks up and reads the words. It employs a camera mounted on a rather thick ring and reads as you go, allowing you to set your own pace. It will also notify you if you deviate from a line or read the end of a line.

Scanmarker Air Pen Scanner - OCR Digital Highlighter and Reader – Wireless, which claims to help people read better and faster, costs $129 (Rs. 16,168).

3. Scan-able glass (used in specs)

A scan-able glass looks like a black glass with a camera base scanner. This camera can tell which person is standing in front of the glass. This scanner not only recognises faces, but also reads what is on the paper. OrCam MyEye 2.0, for example, claims to be a revolutionary, wearable and voice-activated vision device, which costs $3200 (Rs. 401,085).

4. Braille display smartwatch

Smartwatches are common to see in our daily lives. Braille smartwatches are newer innovations. These are phones that display the time, read out messages, and indicate which contact is calling, among other things. Their dot features display Braille.

Four rolling digits tell the visually impaired people the time of the day. The Dot Braille smartwatch uses the smallest Braille cell technology in the world, developed by Dot Inc. and costs around $ 490 (Rs. 61,416).

5. Virtual reality headsets

Virtual reality is also being used to help people with low vision. Instead of immersing people in surreal experiences, these VR headsets recreate a virtual copy of the real world adapted for perception by people with vision impairment. To help them navigate the world more independently, the device comes with functions of a smartphone and a VR headset combined. The headsets are available for a range between $10 and $100.

Experience of Assistive Technology Users

The most used translator in Nepal is Duxbury Braille Translator (DBT), which is also used by the world’s leading publishers. Duxbury Systems support over 170 languages in Braille. The cost of the device that can generate literary, mathematical, and technical Braille content costs Rs. 83,000. It can be ordered from USA.

Most schools use the Duxbury software. Several free tools are also available for use in schools.

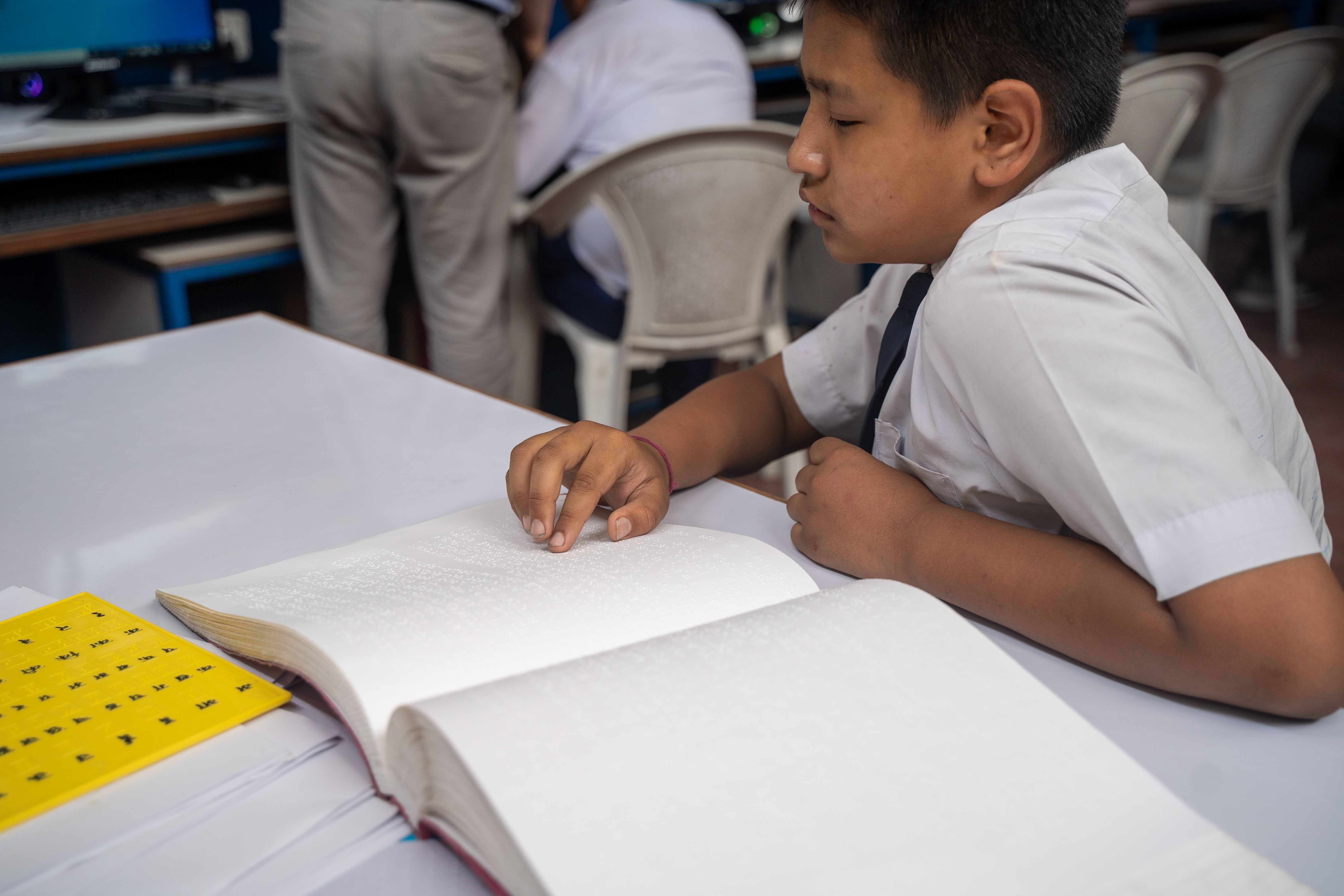

Children reading with their fingers, feeling the differences of dots in Braille, are generally slower than readers using their eyesight to read. Yet many learners with vision problem have overcome their hurdle and taken their studies far enough to inspire others.

Manisha Rai, a 22-year-old Braille teacher and BA Psychology student at RR college, has taught Braille to children from kindergarten to grade one.

“A sound foundation is necessary for their uplift because each learner has a distinct learning potential,” she said. “I carefully coach each student, one at a time, paying attention to help the student deal with a particular learning issue.”

Despite her vision impairment, Sabitri Poudel is pursuing her Master’s Degree in Public Administration at Tribhuvan University (TU).

“In the past, Braille books would be few in number. Each school needed at least one Braille printer,” she recalled.“Now we have more options -- we must adapt to technologies that are universal and effective.”

There are pluses and minuses of old and new technologies. For example, Braille is old and powerful, but its reading speed is a concern for learners. The speed depends on their activity, goals and learning environment. People who acquire Braille competence before the age of 10 are said to be better readers than those who learn it later.

“Laptops are convenient to use but have a short-term impact, unlike Braille which is more effective on the spot and may be sustained over time,” Sabitri added.

Schools, including the Laboratory Higher Secondary School in Kirtipur, Kathmandu, are taking advantage of the technological advances. Founded in 1956 A.D, the Lab claims to offer special facilities for students coming from different backgrounds and corners of the country.There are 46 visually impaired students at the school, which envisions itself as a world-class knowledge centre.

“We have enough musical instruments, but we lack other resources, trainers and learners,” visually-impaired music teacher Ramesh Subedi said. “We need special electronic documents to read from because an equivalent book will be quite heavy and large for us, sometimes covering the entire bench.”

On the positive side, Subedi added that the majority of these children were already winning tournaments and medals or getting interviews for their talents.

Nepal’s Census-2011 has reported a 1.94 per cent disability rate. Globally, one billion people, or 15% of the world’s population, experience some form of disability, and disability prevalence is higher for developing countries, according to World Bank.

Compared to other countries of South Asia, however, Nepal has better facilities for people with disability, according to Prakash Ghimire, Executive Officer of the Nepal Association for the Welfare of the Blind. “Study materials and gaming materials are free for those who are visually impaired. I believe that while numerous NGOs and INGOs have donated resources to schools, they are not being properly utilised.”

Based on the World Bank report, among disability types, physical disability ranks first at 36.3 per cent, followed by Blind and Partially Sighted at 18.5 per cent. Speech-related, mental, and psychosocial disabilities affect 11.5 per cent, 7.5 per cent, and 6.5 per cent of the population, respectively. Deaf-blind people, on the other hand, have the smallest population at 1.8 per cent, followed by intellectual disability at 2.9 per cent. The literacy rate of people with disabilities is estimated to be around 20 per cent, compared to 65.9 per cent for the overall population.

Easily availability

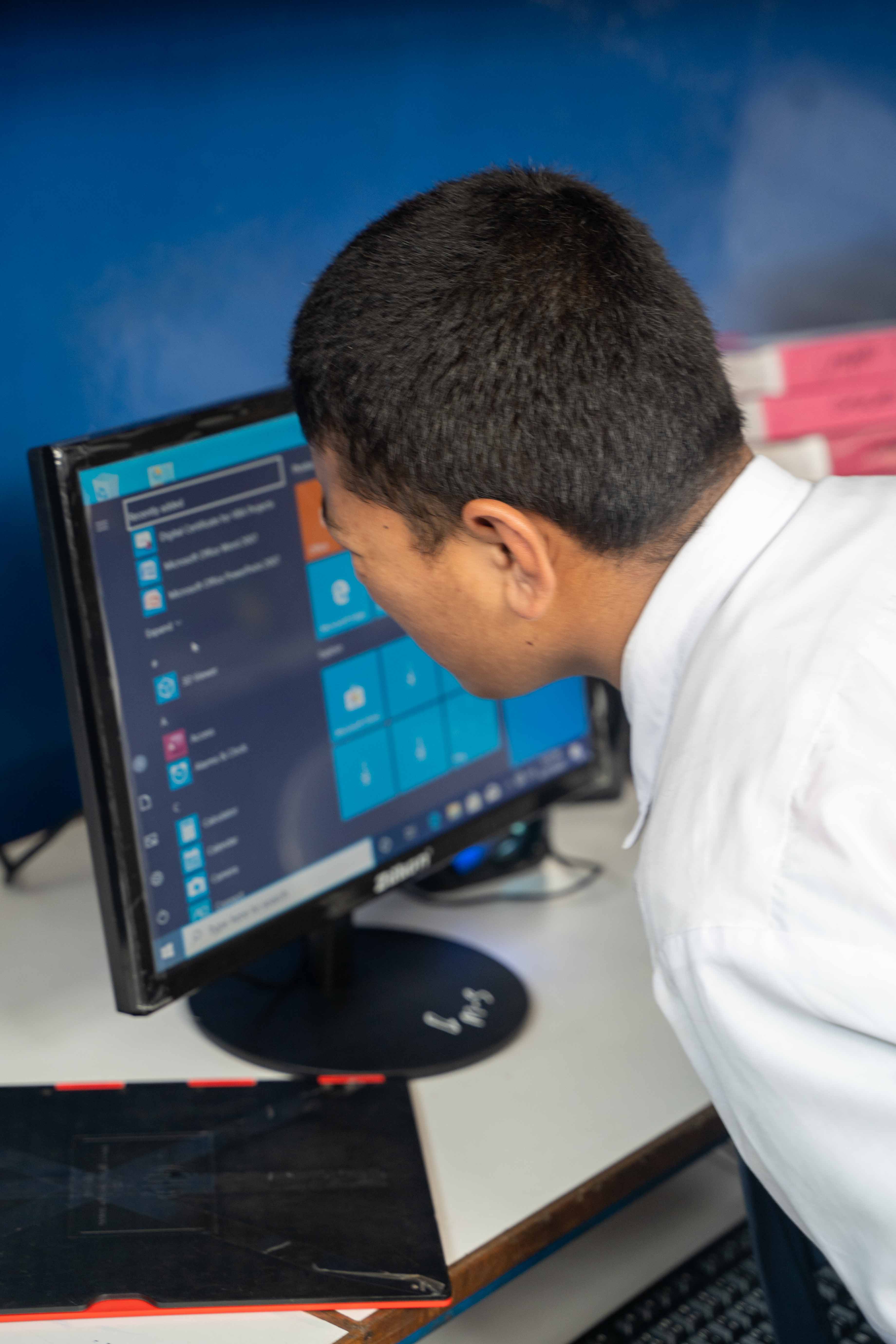

Most people are unaware they are using assistive technologies, anyway. Screen readers, magnifiers, and similar features are included in PCs, smartphones, and tablets. They are more useful for visually impaired and low vision users. Portability and versatility make laptops or notebook computers more attractive choices.

People with vision problems find screen access programs more useful because they generate spoken, synthetic speech, using the PC's soundboard and loudspeakers or headphones. While the users write data on the keyboard or navigate the Windows operating system or an application, the programs read out what is displayed on the screen loud.

“We have a lot of materials available, but we need machines that manufacture books and computers,” said Sita Gyawali, a Nepali teacher, who is also the first visually impaired Master’s degree holder. “We need new technologies in the educational system, such as audio and video materials that cost some Rs. 60-70,000. We're seeking project sponsors by contacting a few people; some are keen, but others aren't. As a result, we are falling behind in this area.”

Narayan Paudyal, a Social and Braille Teacher, said Braille books should not be updated every year as the white paper, the stylus to write in slate, is costly, at 3 rupees per page. “Students use an average of 5-6 pages per day, which makes it roughly 200 pages for classes throughout the day.”

Talking of constraints, Paudyal said, the school lacked enough space for Braille training, book printing, and computer use. “We need buildings, rooms, administration offices, and staff to be able to manage everything properly.”

At another level, he added, even educated guardians need re-education so they send their children with special needs to schools. “They are embarrassed about the special needs of their children, due to a lack of proper understanding, and they hesitate to send their differently- able children to school or society.”

Shree Purwanchal Gyanchakshu School, a resident special school for visually impaired, poor vision, and multi-handicap children in Dharan, east Nepal, has 55 students at grades going from 6 to 10. They use computers and Braille letters with ease.

“Each of these students has a computer for use,” Principal Pramod Bhandari said. “They use blind-friendly software such as NVBA and Jahaj to download courses. We’ve trained our studentsto use text translators for homework and exam.”

Assistive devices are getting ubiquitous among people with vision problem as they engage with the world around them, in daily living, education, and work. Some are low-tech items such as large print books and others are computer software, of science fiction fame of the past.

Braille books, slates, and styluses are readily available and relatively inexpensive. Other IT materials, in addition to Braille, are widely offered in the blind classrooms but teachers are still reluctant to switch to technology-based teaching.

When asked, most teachers said that learning Braille at a young age was beneficial, but that as the technology advanced, they needed to learn new skills and adapt to new environments.

Computers are already common in classes for teachers and learners to interact with the aid of presentations, music, videos, and animations.

Enter assistive devices – they are opening new vistas for the vision-impaired, increasing their access to a variety of sources, on and off the computer and the Internet, helping them acquire new skill, information, and ability in a dramatically different way.