Science & Technology

My visit to BP Koirala National Observatory at Nagarkot was long due. I first had a virtual glimpse or two of the observatory while watching Ajako Bigyan, a science show, as a 7th grader.

When I visited the observatory, I was doing my Astrophysics project as a student of B.Sc, with my classmates from Tri-Chandra College.

We had postponed our trip by a week due to power outage at the observatory. We were then talking about the spilt milk -- if it were a week ago, we could have observed five planets marching in a line, a rare occurrence that won’t repeat before 2040. Observatories across the world were turning their telescopes to cover the rare phenomenon in the dark sky. Our country’s only observatory was without lights.

On June 30, around 8pm, a messenger notification came from our project and trip coordinator: “The excursion has been planned for tomorrow, we will be leaving college at 1pm if everything goes as planned.”

Though we had missed the chance to watch the sky march of our planets, the stars were aligning themselves for our spectacle. I was going for stargazing on the day NepalMinute was also going live. These two events of my interest were contesting for space in my fleeting thoughts before I could fall asleep. I knew I needed enough sleep to stay awake and gaze at the dark sky.

The morning was hectic. I gave final touches to my stories for the news portal. At the same time, I was packing my bag. I then rushed to the newsroom for the launch of NepalMinute. Soon after the launch, I left the newsroom to catch the bus to Nagarkot at New Baneshwor.

While waiting for the bus, five of us would look up to the sky and speculate about whether the clouds would clear.

“Can we trust the weather forecast?” a classmate asked.

“I have doubts,” another replied.

The next one was praying: “God, please don’t make it rain; we are expecting to see the planets tonight.”

The bus came to pick us in a typical ‘Nepali time’, only 30 minutes late. Past the busy junctions and traffic jams of the cities on the way, we climbed the hills of Nagarkot. It was soothing and fun to see the greenery for a change. The bus added to the fun, blowing its horn in the tune of Gori Tera Gaon Bada Pyara of the Bollywood movie Chitchor, or the heart stealer, fame.

Shouting and laughing at every turning as the driver pushed ‘Gori Tera’, we reached the National Observatory of Nagarkot at 3:30pm.

Observatory manager, Saroj Raj Shahi, welcomed our jumbo team of 15. We put our bags in the room and had light food. Our Head of the Department of Physics Ishwar Prasad Koirala and our project supervisor Raj Kumar Pradhan joined us there.

Saroj sir, the observatory manager, gave each of us a ‘SkyMap’ of July and started briefing us on how to use the map: “The north faces up, east is on the right…”

I was working on globular clusters, gravitationally bound dense star clusters. My search yielded nothing, no luck this time!

He described the observatory and telescope: the specifications, the capabilities and so on.

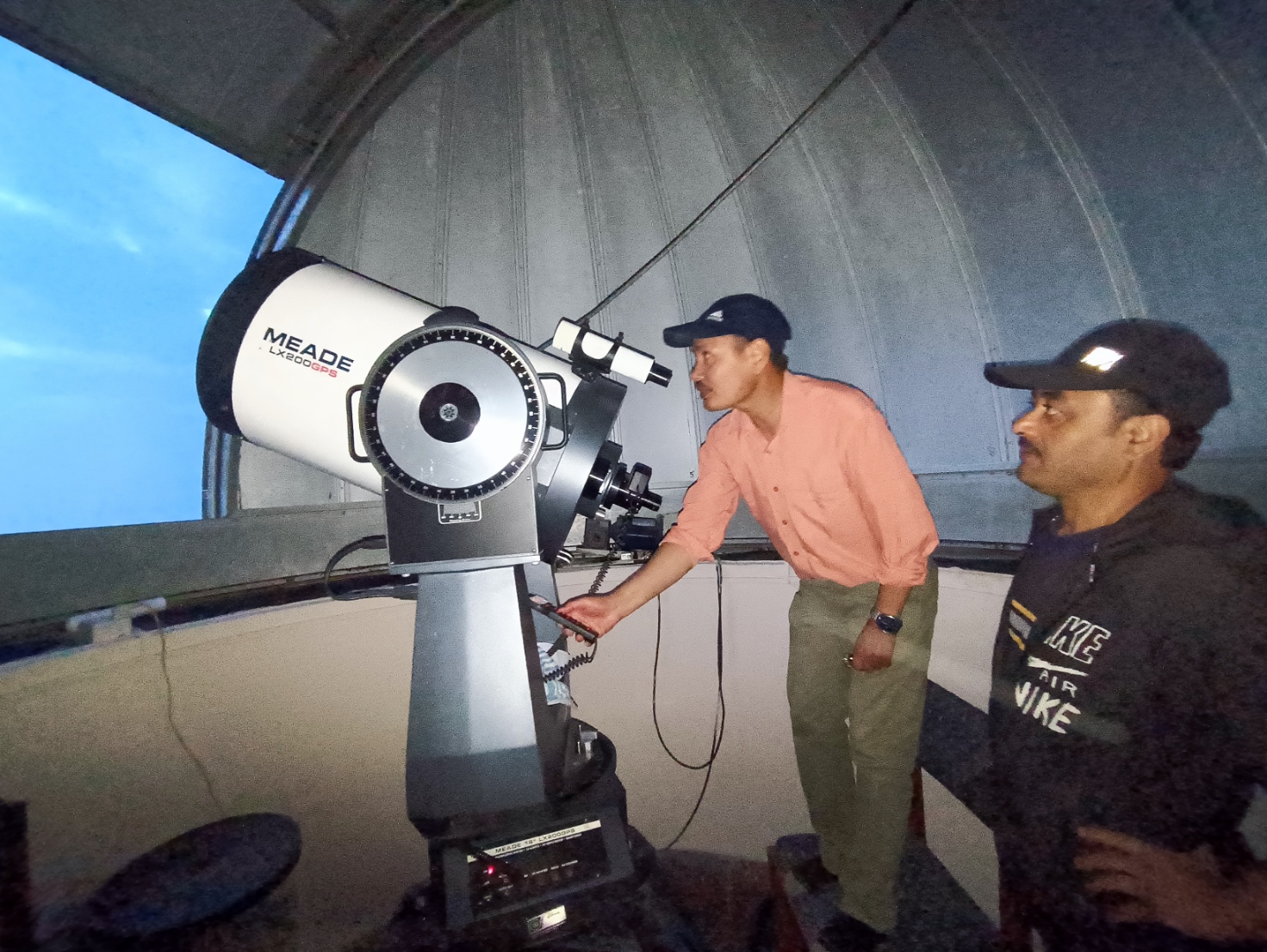

The only national observatory of Nepal is located at a height of 2115 metres above the sea level, about 30km from Kathmandu. The ‘Meade 16" LX200GPS, Schmidt-Cassegrain Optical Telescope’ has a lens of 16 inches in diameter, small by today’s standards.

“Though small, it is still good to observe and do small researches on the moon’s crater,” Saroj sir said.

The telescope is connected to GPS and can auto-track the objects moving in the sky. The telescope also has some add-ons such as charge-coupled device (CCD) and spectrograph to enhance its capacity. CCD converts the optical signals to digital forms and spectrograph helps in the analysis of chemical contents of the objects with light.

During the briefing, Saroj sir talked about how light pollution affected stargazing from Nagarkot.

“You can’t see dimmer objects in the sky towards west, above the Kathmandu valley. “Even in Nagarkot, the sky is glowing.”

Was it possible to control the lights there? Someone asked.

Saroj sir laughed it off: “Science has taken a backseat here. This place is a tourist attraction. A lot of hotels have been established here, a lot of investment.”

He said: “You can’t really observe the western skies below 45 to 50 degrees of ‘declination’ due to light and also the air pollution. And unfortunately, on the eastern side, we have the view tower hill, so we are limited to 50 degrees on that side as well.”

1657277349.png)

In other countries, he added, construction and development inside a certain radius of the observatory are restricted, but here we are just limited to the building perimeter. “To use larger telescopes, we need to search for a better area.”

For research and observation, one needs to select specific objects in a small patch of the sky.

“This telescope is okay for moon and planet observations for small experiments,” he said.

Now we were off to watch the moon. The weather was fine but the sky was not dark enough for stargazing. Having listened to the capabilities of our observatory, we hyped down our sky gazing tour.

But to my surprise, the moon was crescent, yet the view was beautiful. We could see the moon zoomed in so big that every crater was visible.

I nearly forgot to pose for social media and quickly asked Madhu sir to click my photo. After everyone had seen enough, we went for dinner.

When we returned, the weather was foggy. I could barely even see Raj Kumar sir, standing just 10 metres away. Believe me, the ambience was like that of a horror movie set -- fog, dark, blurred vision, and little glows of light here and there.

Now the waiting game began, all of us hoping for the weather to clear. Boys cranked the volume in their little Bluetooth speaker to the full and started dancing. At 1am, some went to bed. Five of us danced nearly the whole night, waiting for something to appear up in the air.

No luck! We observed nothing but the moon playing hide and seek, she was waiting for her lover Kuekuatsu, we were yearning for clear weather.

When to visit and what to expect when you visit the observatory?

The best weather for visiting the observatory, as Saroj sir said, is after Dashain and Tihar, during winter. The weather is clear and the visibility then depends on the pollution level. But there always remains a chance of light snow and chilly weather -- you will do well to pack your jackets for that time.

Contrary to the belief in the world of technology, where everything is getting miniaturised, the larger the telescope gets, the better it becomes for stargazers.

The telescope we have here is not of the ‘western’ standards. These days, something less than a few metres in diameter is considered small, in that regard, ours is very small.

Yet, with our telescope, craters of the moon are visible in high detail, and the shape of planets can be seen as in photographs, like the rings of Saturn, and clouds of Jupiter.

But the stars are seen just as blobs of light, nothing more, as Saroj sir said.

“Binary stars and the star clusters are seen as a single source. The telescope does not have enough resolution to differentiate the objects.”