Nature

Welcome to Kathmandu Valley of 1700 years ago when water spouts were engineered to never run dry until they hit a modern snag.

The water supply system of the era, called the hiti, was made up of eight parts: rajkulo or royal irrigation canal, pond, aquifer, navimandal or intake structure, waterway, hiti-ga, hiti-manga and exit.

The hiti system harvested water from underground aquifers and ground intake structures to ensure round-the-clock water supply.

Upstream ponds collected rain water, feeding rajkulo and filling aquifer. These intake structures were intricately placed and connected with the underground water conduits, carved out of timber or made of terracotta gutter called hitidun.

The hitidun finally manifested as water spouts or hiti-manga.

The modern piped-water system, introduced in Kathmandu Valley in the late 19th century, badly hit the hiti, that is, the system of dhungedhara in Nepali.

The hiti records date back to the Lichhavi era, about 1700 years ago. The water supply system was a developed form of work from the Kirat civilisation. The system expanded in the Malla period.

A response to the need of the ancient civilisation, the system sustained a continuous flow between ground and surface water.

Commissioned by various rulers of Ancient and Medieval Nepal, parts of the hiti system have lasted long enough until now.

“Only the modern period has lost some parts of the system,” according to engineer Padma Sunder Joshi, an urban planner, who has been doing a research on the hiti system for two decades.

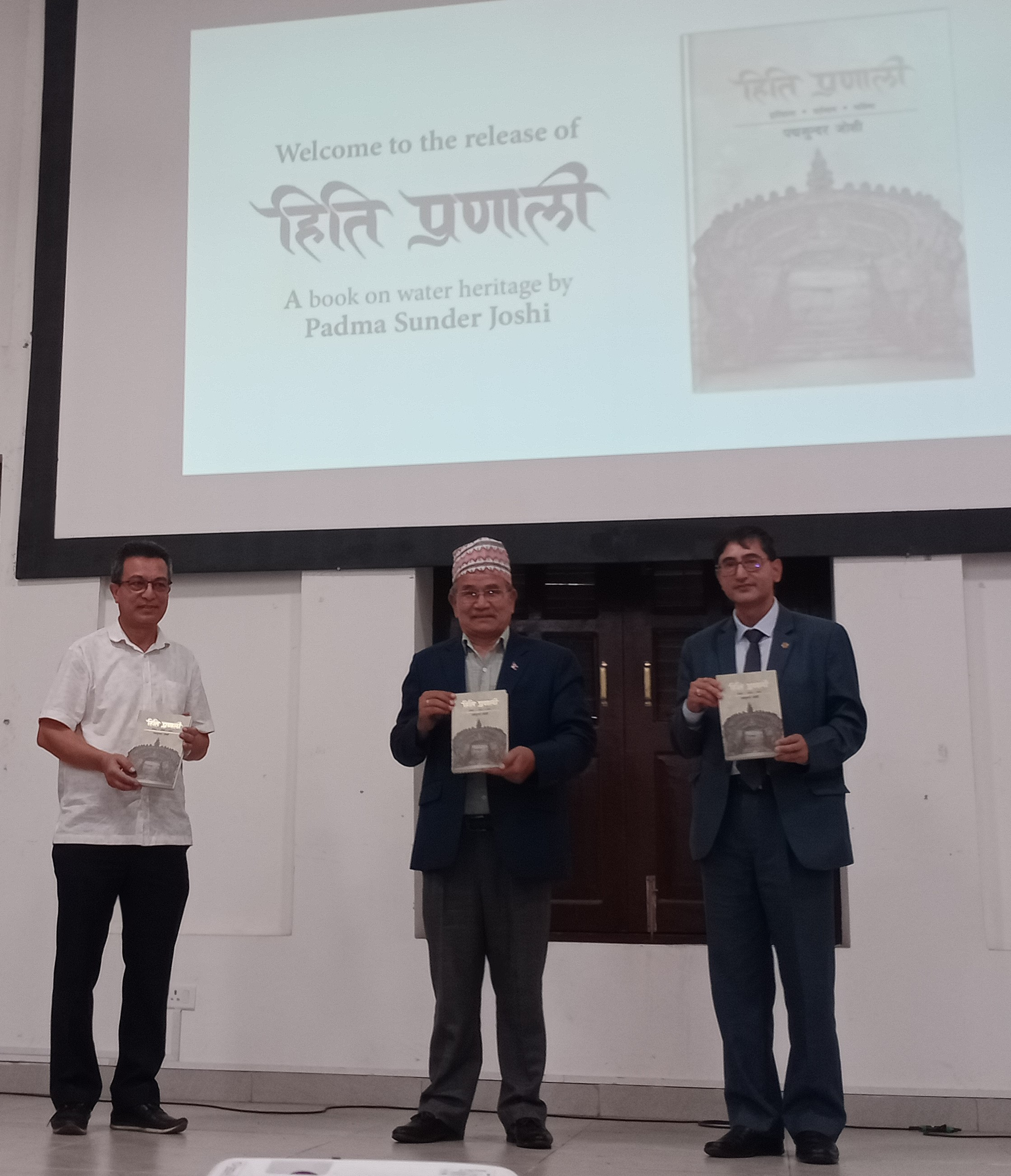

His book, Hiti Pranali, a product of his extensive study on the ancient water supply system, was released recently.

In his book, Joshi noted there were 40-50 traditional settlements in the valley.

Environmentally, the settlements were developed to run a cycle of three parts: human settlement, agricultural area and natural base.

As settlements were at heights, they would lack water in the dry season, a challenge for water management, said the author. Another challenge, he added, was the fear of landslides in the rainy season.

“Hiti is also the name of the infrastructure born out of this need,” Joshi noted.

The records found in Gopal Raj Vamshavali, an old manuscript, suggest that the oldest hiti system was established by Lichhavi king Brishdev in Syenagu Bihar of Swayambhu, according to Joshi.

“The oldest living hiti system is hiti-manga of Patan, made by Bharavi, the grandson of King Mandev in 570 AD,” Joshi said.

What hit the hiti then?

Kathmandu Valley has more than 573 hiti systems, according to a research by the Kathmandu Valley Water Supply Management Board.

“Of these, 35 per cent are running, 49 per cent have dried up and others are lost.”

Unmanaged and unplanned urbanisation is the main reason the spouts of the valley have dried, according to Joshi.

“Both the technical and social sides went wrong. On the technical side, the reservoirs of the spring were drained and rajukulos and ponds were lost,” Joshi said. “Extensive construction of private tube wells, drinking water and sewage drains, among other structures in the way of the groundwater, became huge obstructions.”

The mapping of the source of the spouts hasn’t been done which is also why the hitis weren’t saved, he added.

“Likewise, if we look at the social side, the disappearance of traditional arrangements of hiti management, such as the collapse of Institutions like guthis, or trusts, the hitis got lost.”

Joshi said that the introduction of the drinking water pipes and taps covered the hitis and the centralisation of the urban services created problems in their conservation.

Among the people of new generation, he added, rules of religious faith were weakening, which, to him, was why there was less concern about keeping the hiti clean or saving it.

The way to rehabilitate the hiti

The only way to rehabilitate the hiti is to revive the system as a whole, according to Joshi.

In the valley, of the 233 ponds that existed in the past, 40 were lost, with only 193 remaining there.

“These ponds should be saved and the lost ones should be revived, along with the rajkulo,” he said. “But without the involvement of the local community, the hiti can’t be saved.”

Joshi’s proposal to revive the hiti puts mapping the system on top, alongside declaring it a national heritage, with a proper law, without its politicisation.

It includes separate sewage systems in the valley, with rain sewage and exit sewage.

To ease water supply, 25-30 recharge wells have been made in Lalitpur in different places, which, he said, was a big effort.

“The recharge well was made with a view to have water at least in the well, if not in the spout,” said Joshi.

Talking about hiti at the book launch, Lalitpur Metropolitan Mayor Chiribabu Maharjan accepted his failure to save the traditional water management system.

He said the main reason he failed was political, because he couldn’t get any help in his efforts to save the system.

“I have to accept that the metropolis, and I, did not succeed in getting the hiti running water,” Mayor Maharjan said. “We will keep trying and working. But, I know, we won’t succeed until the whole system is revived.”