People

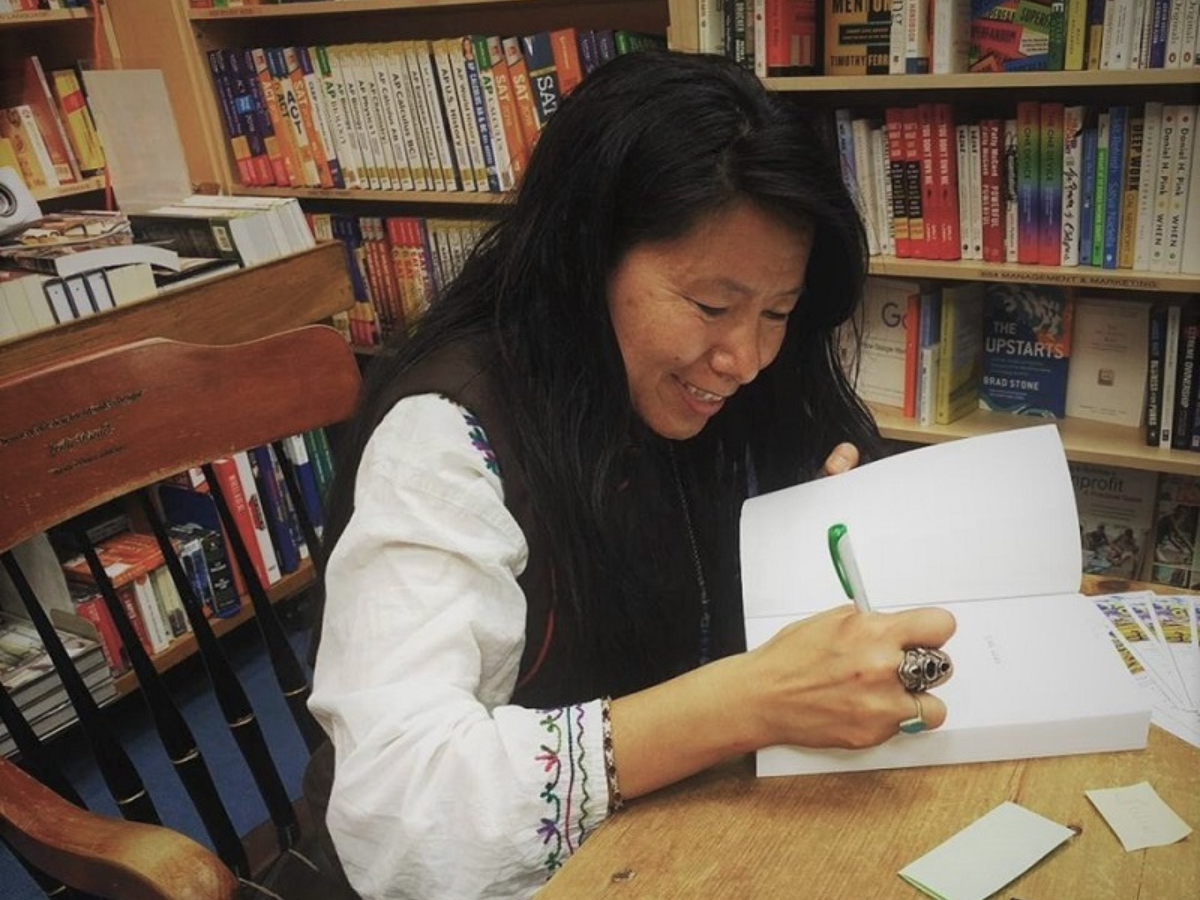

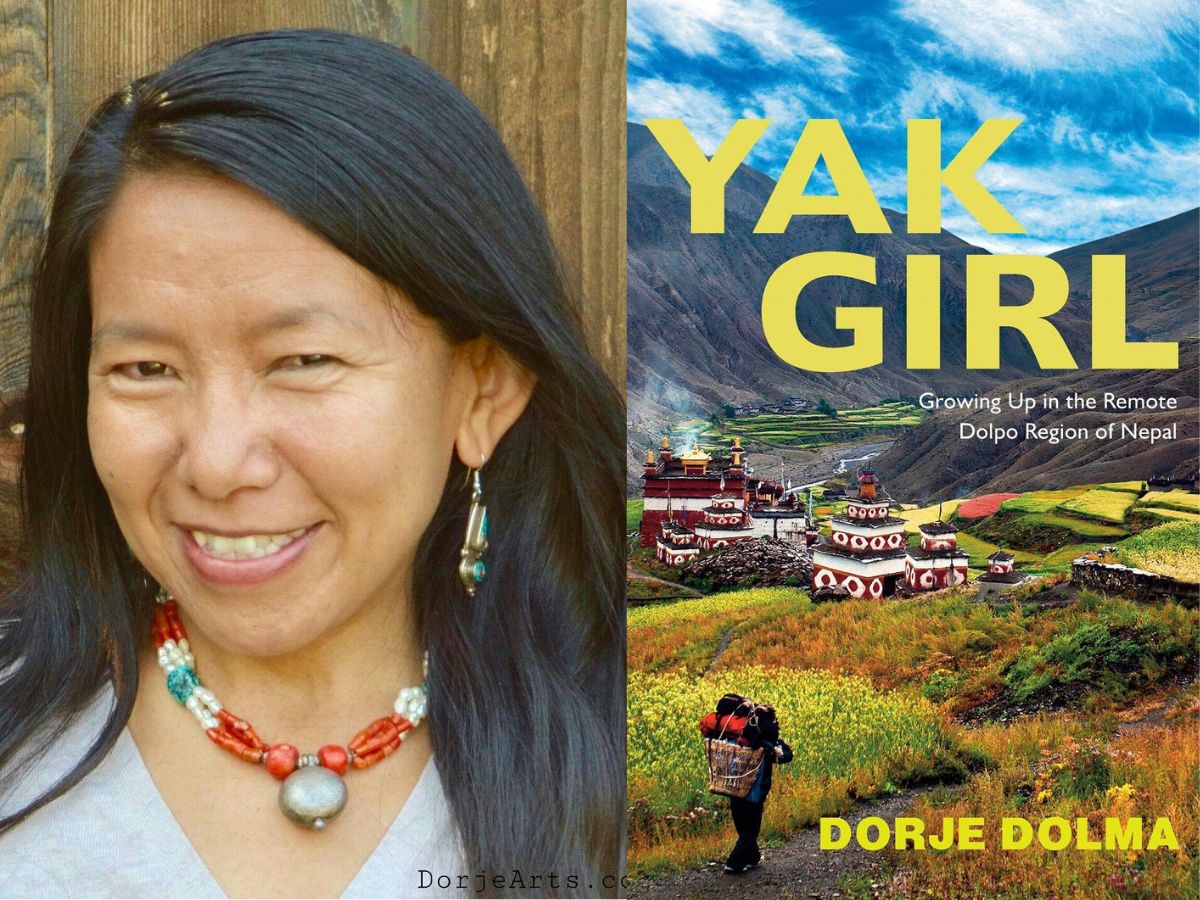

Dorje Dolma is the first woman writer from Dolpo, a small village in western Nepal. She was suffering from scoliosis from a young age and travelled to Kathmandu to receive treatment. With no luck, she found an opportunity to travel to the US and has finally been cured. Today, she is a successful writer, speaker and artist.

She released a book ‘Yak Girl: Growing Up in the Remote Dolpo Region of Nepal’, which is a memoir that narrates the story of a girl living her life in the remote and undeveloped region of Nepal near the border of Tibet.

Dorje, how was it growing up in Dolpo?

I was in Dolpo until 1994 when I was about 10 years old. It is a remote village at 13-14,000 feet. There was no electricity or even any roads. The only modern things were a radio, a cassette player, or a flashlight. It was very isolating. I was just surrounded by a lot of mountains and rivers and animals. And I didn't know that there was a whole new world beyond the mountains.

But when I was about nine years old, I started to see more of the modern world. I started seeing travellers and some trading businesses too. More and more Dolpo people would go to cities and travel, or I would hear stories about the city lifestyle, and I didn't even know what a school was.

As girls, we just didn't really think about going to school or learning how to read and write. And most of the girls that I knew, my friends, the older ones that were 13-14 years were being trained in cooking and weaving. This meant that they were going to get married and are preparing to be good wives. But I had my own bigger issue, I had a life-threatening health issue - severe scoliosis.

How and when did you discover you had scoliosis?

When I was eight or nine, somebody noticed a major lump on my back. And at that time, nobody really knew what to do other than the fact that I might not survive.

Along with not having schools, we didn't have clinics either. All we had were the traditional herbal medicines and my father was a doctor in those medicines. We can't do anything if anyone has any major health issues.

One of the tragic parts about growing up in Dolpo is feeling a lot of hopelessness because we lost so many people. I mean I've lost a lot of my siblings, family members, just from getting a simple illness like a cold. And that was really hard not knowing what to do when somebody got really sick and can’t be taken to the hospital in time. This would get worse, especially in winters. So, it was really hard to see children and elders get sick and get no help.

Dolpo is a small place, as you said, so I am sure the word would travel quickly there. How did people react to your health issue?

I think once I found out about my own health issue, I was focusing on surviving. Everyone was telling me that it was so sad I might die young. Another thing I struggled with is once you have some kind of disability, people just right away assume you're not able to do anything and you become extra weak. And so, once they found out I had a back problem, and they were like, “Oh, you know, you can't do this. You shouldn't climb the mountain; you shouldn't do this or that so often.”

But before people found out [about my back], I was a herder. So, I was going up to the mountains at 18-20,000 feet and herding with hundred goats and sheep and facing wolves and snow leopards. And yeah, it hurt my back. I was struggling to climb sometimes. But I really enjoyed being out in nature and challenging myself.

So, once I told them about my health, and people kept telling me I couldn't do those things, I sometimes didn't tell my friends and family members that I wasn't feeling well, I kind of kept it to myself and just kept doing my job.

Is this where you and your family went to Kathmandu?

Yes. Till about age 10, I stayed in Dolpo, and then I trekked down from Dolpo to Kathmandu with my family - my parents and siblings. We walked the entire journey and it took us a month.

The whole idea was to see if there's a way to get help with my back in the city. We saw some they just said that it's too dangerous for them to do the surgeries because my spine, instead of being straight was curved, like a C shape.

Because of the journey, we didn’t have enough food or money left. At least in Dolpo, we could go ask our neighbours for help or trade blanket for rice or something like that, but nobody in the city does that. So, if you don't have money, then it's really hard to survive. My family and I had even begged. I also tried to get into schools in the city to see that if I stayed in the city, maybe eventually someone will help me, but the schools back then were full, or they were really expensive.

A lot of people in the mountains, especially in Nepal, by March - April, they go back to the villages to work in the fields. We were planning to go back, but I really didn't want to go back. I knew that going back meant my life would definitely be cut short.

So, did you end up going back to Dolpo?

As we were about to give up and return to Dolpo, I came across the Rokpa Soup Kitchen, where we were grateful for Rokpa’s free hot meals. Rokpa International is a non-profit that has been helping people in Nepal for over 30 years, providing shelter, food and education for those who need them the most.

When I was about to give up and go back to Dolpo knowing I will not live long without treatment for my back, I met Lea Wyler, one of the founders of Rokpa. She was at the Rokpa Soup Kitchen one day and asked her if I could go to school because, at that point, I thought if I do survive, then I want to go to school. Rokpa was my last resource. Thankfully I became one of the Rokpa kids and was allowed to stay in Kathmandu and go to school instead of returning to Dolpo. At the Rokpa Soup Kitchen, I met my American family who later brought me to America so I could get the surgeries I needed as soon as possible.

It was all about 15 minutes of my time trying to have the courage to ask for help. And it just changed my life.

What did the doctors in America say?

Doctors in the US suggested they could indeed help me. I came to the US in 1995 and I had four surgeries. It was a very challenging, risky set of surgeries. I am thankful I could make it to the US in time as it turned out I only had two years to live without operation. The scoliosis was crushing my lungs and I was having trouble breathing.

Anyone can have scoliosis, but most parts of the world people get an early check-up before it gets worse but for third world countries or remote areas of the world like Dolpo, without proper health care and yearly medical check-ups, the condition can become life-threatening.

It’s been like 25 years. I'm thankful to be alive and even write a book about my experience and share it with others.

You are the first woman writer of Dolpo. Could you tell me about your book?

One of the main reasons I wrote my book is to advocate that we do need money for research for education and health care in remote parts of the world.

I talk a lot about Dolpo because if we can somehow find ways to provide healthcare and education at 13,000 feet, then that could definitely be done for other remote parts of the world as well. I just wanted to share my story to inspire people to learn more about this region and the people. And that these people have the same desires as the people living at places where you do have the access to stores, access to school choices, access to health hospitals, and all those things, things that are as basic as electricity.

Putting my personal life out in the world wasn't easy, but I just want people to really understand what's going on. I don't want people to not know.

What is next for you?

I am keeping it open. I would like to write. I think writing is telling a story and sharing stories is just another way for people to understand and learn from each other. So, at the moment, I'm just keeping it open and exploring writing and art.

(A slightly different version of this article first appeared in South Asian Today. Read here.)