Life & Health

By Sabitri Dhakal & Suman Malla

Last month, anti-smoking campaigners and health policy advocates perked their ears when the Kathmandu Metropolitan City reintroduced the ban on the consumption of all forms of tobacco products in public places.

The latest ban took effect on September 17, following a decision by the eleventh municipal executive meeting. “The ban on tobacco consumption in public spaces has been imposed to protect public health,” the KMC notice says.

The Kathmandu metropolis intended to draw inspiration from the laws of its sister cities in developed countries. It is a question of catching up with a delay that has placed Nepal at the back of the pack in the global fight against the ravages of tobacco consumption.

Nepal signed the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (WHO FCTC) on December 3, 2003. After its ratification on November 7, 2006, the country became a party to it on February 5, 2007. Based on the WHO FCTC, the government has enacted laws and procedural documents aiming at tobacco control. The Tobacco Product (Control and Regulatory) Act 2011 is the primary law governing tobacco control in Nepal.

Smoke-free zone

Under the 2011 Act, public places where smoking has been banned include hospitals, health institutes, public offices, public transport, court buildings, educational institutions, libraries, and auditoriums.

The ban also applies to hotels, motels, resorts, restaurants, bars, dining halls, canteens, lodges, hostels, guest houses, stadiums and sports facilities.

On the face of it, the policy sounded so sweeping that it could represent what experts refer to as the ‘endgame’ in the fight against tobacco.

Ban on smoking appears to be holding on public transport. But restricting the smoking and chewing of tobacco in public spaces remains a big challenge for the metropolis.

One month after its reintroduction, the KMC ban on smoking and the use of tobacco products in public spaces seems to have gone up in smoke. Sights of people puffing cigarettes with impunity are still quite common.

A visit to a corner teashop near one of many colleges in the valley would lay bare the ground reality.

During a break between classes, a small group of college students were spotted smoking outside a tea shop adjacent to their college entrance in New Baneshwor.

One student was hiding away from public glare and smoking, but another was enjoying his puff out in the open. The student did stub it when pointed out by a volunteer. But not before taking one last long drag.

As per the 2011 Act, the sale of cigarettes and other tobacco products is illegal within a 100-metre radius of educational institutions, healthcare facilities, childcare centres, and old-age homes.

The KMC has also imposed a fine of Rs 100 against anyone flouting the rule.

“People are smoking as the ban has not been implemented properly. The need is to create awareness among people,” said a BBA second-year student, requesting anonymity because of the issue's sensitivity.

Despite the KMC ban on the sales of cigarettes and chewing tobacco, the student alleged that such items are readily available near the college gate.

“When one can easily get the cigarette on the gate, it is impossible to implement the ban,” the student said. “Monetary fine is perfect, but the need is to ensure that cigarette is not available in the open.”

Walk about half a kilometre down. Across the face of the Civil Service Hospital’s main entrance, the visitor would find street hawkers lining the pavement. Besides bottled water and other stuff, they sell cigarettes and smokeless forms of tobacco, including Gutkha – usually sold as a mouth freshener.

While most of the hawkers declined to speak, one was forthcoming – on condition that NepalMinute does not reveal his identity. "Smokers will smoke come what may," he said, adding that he hoped to continue selling about 20 packets a day.

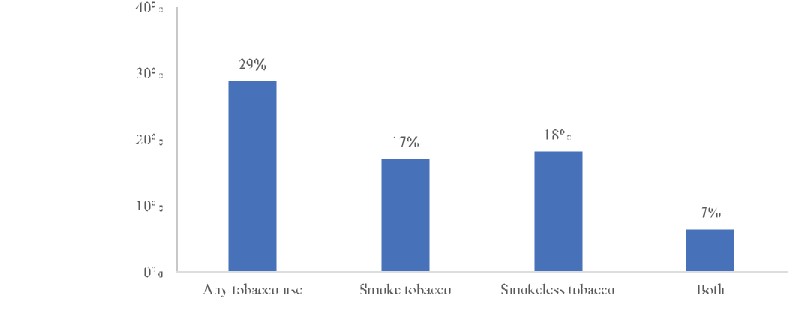

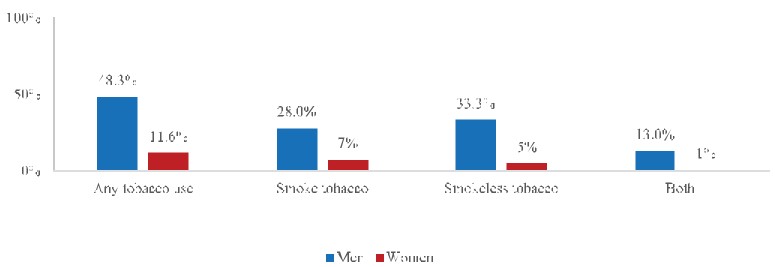

According to the Steps Survey 2019, conducted by the Nepal Health Research Council, 3.8 million people in the age group of 15-60 years in Nepal use tobacco in some form – smoked or smokeless. At 48.3 per cent, male have over four times higher prevalence than 11.7 per cent of women. This is higher than that of India and Sri Lanka. Only Myanmar has a lower prevalence than Nepal in the region.

While the prevalence rate is decreasing for smoking, it is increasing for smokeless tobacco, suggests a recent report.

According to the Steps Survey, 17.1 per cent of adults which equates to 2.8 million people smoke tobacco products in the country. Around 3 million people, 18.3 per cent of adults (33.3 per cent of men and 4.9 per cent of women) use smokeless tobacco.

"KMC’s decision to ban gutka is a very welcome and encouraging step in controlling oral tobacco use,” said Dr Bijesh Raj Ghimire, medical director and senior consultant medical oncologist at Nepal Cancer Hospital in Harisiddhi, Lalitpur.

According to him, while Gutkha and Paan masala manufacturers claim they are tobacco-free, they have betel nut, which is also a carcinogen.

"Tobacco products in attractive sachets are fast replacing traditional forms of chewing the betel leaf with all the other ingredients," Dr Ghimire said, warning that the use of tobacco products by youngsters, if unchecked, would lead to a major burden of oral precancerous conditions like sub-mucous fibrosis and oral cancer.

Tobacco use leads to more than eight million deaths worldwide each year, according to the World Health Organization (WHO). More than 7 million of those deaths are the result of direct tobacco use, most of them coming from low- and middle-income countries such as Nepal.

The UN health body says that around 1.2 million deaths result from non-smokers exposed to second-hand smoke.

In Nepal, 3.7 million adults (22.5 per cent) are exposed to second-hand smoke at the workplace and 5.5 million (33.5 per cent) at home, the Steps Survey has found.

The metropolis dismissed suggestions that its latest effort to outlaw smoking and tobacco consumption in public places will depend on compliance rather than enforcement.

“We are doing this for the welfare of the citizens, no other reason,” KMC spokesperson Nabin Manandhar had said shortly after the notice – but a couple of days before the ban would take effect. He insisted that there was every reason to believe the ban would get public support. “Compliance on restricting tobacco consumption in public places should not be a challenge.”

Checking the efficacy of the ban is easy.

A closer look at drainage lines along the city’s major thoroughfares would show startling evidence of tobacco products' rampant use.

1666084632.jpg)

Gutkha packets cause more harm to the environment than regular plastic waste because they cannot be recycled and thus are not even picked by ragpickers.

That is another public nuisance that city dwellers confront quite often.

Strewn empty Gutkha packets on the roadsides are found to be the main cause that clogs Kathmandu’s drains during the monsoon months, leading to water logging and traffic jams.

“Most drains, especially those around bus stops in the city, look like mini Gutkha factories,” said Kiran Amatya, former chief of the Sewerage Department under the Kathmandu Upatyaka Khanepani Limited.

According to him, when the mouth of the drain is blocked, water is unable to seep through it, even if it has the capacity to sieve out water.

“This blockage delays the clearance of water from the roads, which in turn causes the roads to be flooded even with a few minutes of rain,” Amatya, the 67-year-old engineer, added. “The ban is a well-intentioned move by the metropolis to safeguard people's health, but its success lies in how effectively it is enforced.”

That is a thought shared by the majority of citizens. And it did not pop up overnight.

Past attempts fall flat on their face

Successive administrations at the KMC have devised an extraordinary and far-reaching set of plans for a tobacco ban but never implemented, public health experts say.

Consequently, all efforts by the KMC administration to make the city’s open spaces a ‘no-tobacco’ zone have fallen flat on its face.

Past attempts by the metropolis to ban smoking in public spaces have drawn little success due mainly to reservations about the practicalities of implementing the ban. The city office created rules limiting advertising, marketing and sales, but implementation was ineffective.

In March 2019, the KMC announced a similar restriction on smoking and tobacco use during Bidya Sundar Shakya’s tenure.

In 2016 the Metropolitan Police Range Kathmandu stepped up action against smoking in public places.

Police had also briefly detained more than 2,000 persons in Kathmandu in June-July 2012 for smoking in public places.

Health experts suggest that a wide-ranging ban, like the one proposed in the capital, should be accompanied by other tobacco reduction measures to maximise effectiveness. One of them is to limit the number of retailers where tobacco can be sold.

Dr Megha Nath Dhimal, a senior research officer at the Nepal Health Research Council, said: "Any new decisions face protests when imposed."

Playing hardball

“It will be difficult for the KMC to make people comply with the restrictions as people might not follow them in the beginning,” he continued. "It's not an easy fix or a light switch to say, 'Ok, let's do it'. It calls for a concerted effort from the government and the tobacco control community.”

A research paper published recently in the National Library of Medicine, the US-based world's largest medical library, revealed that in Nepal, the overall compliance with smoke-free legislation was 56.4 per cent.

The highest compliance –75.0 per cent was observed in government office buildings.

On the other hand, eateries, entertainment, and shopping venues had the lowest compliance at 26.3 per cent.

"To make people comply with the restrictions, the KMC should allocate smoking zones for the public. Or else people will start consuming it anywhere," said Dr Baburam Marasini, former director of the Epidemiology and Disease Control Division, Department of Health Services.

"Tobacco is a very powerful, addictive substance,” said Dr Marasini, suggesting that allowing a buffer period for an implementation plan, community education and enforcement.

“No alternative or safer option to quit smoking has been provided by the metropolis so far,” he said. “This has triggered a backlash from the users and stakeholders who question the city authority on its failure to curb smoking and chewing of tobacco in the public places.”

Anti-smoking advocators, however, press the metropolis officials to play hardball.

Dr Prakash Raj Neupane, a Nepal Cancer Relief Society member, said: “Tobacco consumption will have an adverse effect on health. There is a risk of tuberculosis, high blood pressure, cancer, heart diseases, and diabetes in people who smoke.”

According to the Nepal Cancer Relief Society, around 27,100 people die of tobacco-related diseases in Nepal and 90 per cent of them die of lung cancer. Two persons die every hour due to tobacco-related diseases.

“If the metropolis really wants to make this drive successful, it must walk the talk by mobilising metropolitan police and volunteer inspectors to track down offenders,” said Dr Neupane.

“They can also take help from Nepal Police.”

“Share that on media, then it will be more effective. The campaign should be persistent,” he said, referring to the success story of the campaign against drink-driving in the country. Traffic police started the anti-drink driving campaign in December 2011.

When contacted the second time, KMC spokesperson Manandhar said, "The KMC will do whatever it takes to make people compliant with the 'no tobacco in public places' rule. People know that tobacco consumption is harmful to health. We need people's support."

What about vaping or e-cigarettes?

Also Read: Vaping businesses boom in Nepal

Although restrictions have been imposed on tobacco consumption in open spaces, the metropolis has been conspicuously silent on vaping or e-cigarettes.

"We have not thought about vaping. The number of people who use vaping devices is comparatively low. We need to understand vaping and its side effects," Manandhar said.

Electronic cigarettes – more commonly known as e-cigarettes or ‘vapes’ – have grown in popularity in Nepal in recent years. E-cigarettes do not fall within the scope of existing national legislation on tobacco production, distribution, and use. Yet public health experts worldwide warn they pose significant health risks similar to conventional cigarettes.

According to the WHO, e-cigarettes emit nicotine, the addictive component of tobacco products. In addition to dependence, nicotine can have adverse effects on the development of the foetus during pregnancy and may contribute to cardiovascular disease.

“Smoke-free spaces not only promote healthy behaviours to children and young people, but they also encourage smokers to quit and make it easier for ex-smokers to stay smoke-free,” Manandar said.

"Those violating the rules will be punished,” Manandhar said, advising people to report incidents of rule violations on KMC hotline no: 1180.

Smoking and Smokeless tobacco

|

The Tobacco Products (Control and Regulatory) Act 2011 has divided major forms of tobacco use in Nepal into two categories: smoking and smokeless tobacco products. Smoking includes cigarette smoking along with hand rolled cigarettes (Bidis). Smokeless tobacco products consumed include Gutkha which contains areca nut, tobacco, catechu and sweet flavour, Zarda-Paan or betel quid (rolled betel leaf with lime, betel nut and tobacco), Khaini (flavored tobacco mixed with lime), and Sokha (non-flavored raw leaf of tobacco crushed manually, mixed with lime and rolled in hands before use). |

_11zon1681280198.jpg)